Dementia Health Needs Assessment – Prevention and Care (2019)

This is an assessment of the health needs related to dementia, with a focus on prevention and social care, in Wandsworth, designed with the aim of informing adult social care commissioning activities in the borough.

This document is also available in PDF format: LBW Dementia Health Needs Assessment 2019

Executive Summary

Dementia, owing to increasing prevalence and its complex impact on those affected, is now recognised as a major issue nationally and locally. This needs assessment has been constructed to facilitate informed action in response to dementia need in the borough.

How is Wandsworth affected by dementia?

Whilst five years ago dementia prevalence in Wandsworth was lower than average regionally and nationally, due to a high local incidence rate, prevalence in the borough is increasing faster than average elsewhere. Current data describes a varying distribution of dementia within the borough. The number of people aged ≥65yrs affected by dementia is expected to increase by 47% by 2035. The rate of increase can be reduced with effective reduction in dementia risk factors.

In 2019, the cost of dementia in Wandsworth is estimated to be approximately £70.4m, £27.4m of which being attributable to social care costs. This is expected to increase to £102.7million and £40.1million respectively by 2035.

How well is Wandsworth performing in relation to dementia prevention?

Approximately 30% of cases, attributable to the main sub-types of dementia, are potentially preventable. Wandsworth is performing well in relation to physical inactivity levels, the biggest modifiable risk factor for dementia. However, Wandsworth is performing no better than the rest of London in relation to smoking prevalence and worse than London in some metrics related to hazardous alcohol consumption.

Whilst current health promotion activity does address these risk factors separately, there is currently no coordinated interagency programme to raise awareness of risk factors specifically in relation to dementia in the borough.

How well is Wandsworth performing in relation to dementia care?

Following a diagnosis of dementia in Wandsworth, residents (carers and people diagnosed with dementia) can access support, information and training programmes to equip them with skills to aid in achieving a positive life with dementia. Whilst the pathway to these resources is clear from local memory assessment services, the route from other diagnosing organisations, such as hospitals and private practices and services in other boroughs is less well established.

Following the immediate post-diagnostic period, ongoing support is available via clinical, voluntary and social care services, However, navigating what is available and organising care and transport to attend these services can present a challenge for residents.

Typically, progression of dementia leads to greater care needs. With increasing demand for home care services and geographic obstacles to accessing day centre services, Wandsworth faces a challenge in supporting people with dementia to remain in their homes and communities as their needs increase.

Once care needs develop beyond the capacity of day centres and home-based care, admission to care homes is often indicated. Whilst care beds in the borough are plentiful compared to other Boroughs, they are of mixed quality and produce a high demand for emergency healthcare services.

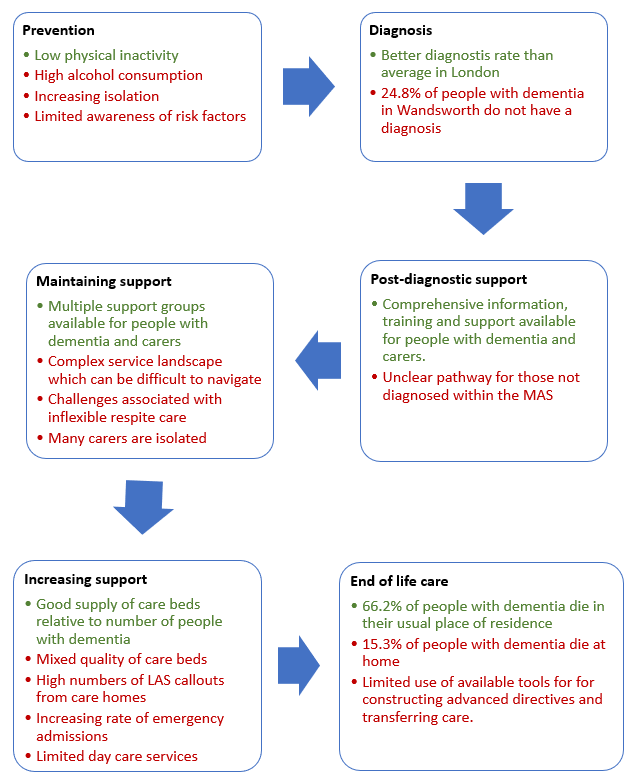

Figure 1: Successes and challenges in dementia prevention and care in Richmond

Limitations to this needs assessment

The perspective of people in Wandsworth living with dementia, or carers for those with dementia, were not sought for this needs assessment due to limited resource availability. Should any work related to dementia follow-on from this work, it should actively consider the perspective of those affected by dementia locally.

Furthermore, the data on many metrics for dementia care, particularly those related to equity of access, are limited. Consequently, it is not possible to achieve any conclusive insights in to service equity in the borough. Consideration of action to resolve this is included in this document’s recommendations, acknowledging the importance of actively redressing inequity through local authority commissioning and the potential for the burden of dementia to be inequitably distributed based on risk profiles.

Overview of dementia

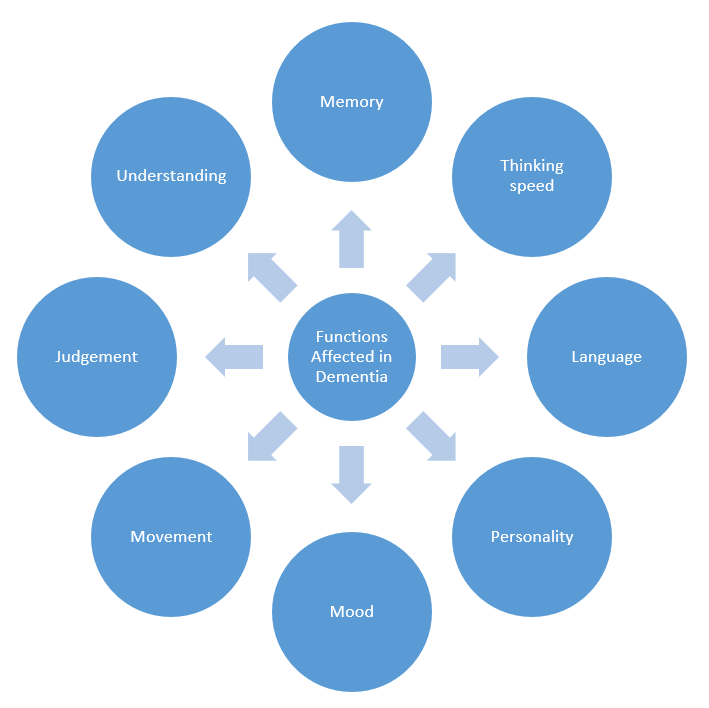

Dementia is a group of cognitive and behavioural symptoms associated with a progressive decline in brain functioning. Figure 2 displays some of the brain functions most commonly affected in dementia. Certain sub-types of dementia present with different patterns of functional decline (see Figure 3).

Loss of any of these faculties can impact on an individual’s ability to independently live an enjoyable and fulfilling life. However, with the right support and care, people can live well with dementia [i].

Figure 2: Brain functions most commonly affected in dementia.

Figure 3: Sub-categories of dementia

| Dementia sub-types |

| Alzheimer’s disease: The most common form of dementia, accounting for approximately 60% of all dementia cases. Alzheimer’s typically starts with impairment of episodic memory and progresses to affect other brain functions.

Vascular dementia: The second most common cause of dementia, accounting for approximately 20% of cases of dementia in the UK. Vascular dementia typically presents with a stepwise deterioration in brain function, occasionally with localised weakness or reduction in vision. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): The third most common form of dementia, it accounts for approximately 15% of dementia cases. DLB is often associated with delusions, hallucinations and transient loss of consciousness. Occasionally DLB can make mobilizing difficult. Frontotemporal dementia (FTD): <5% of cases of dementia are due to FTD in the UK. FTD is associated with gradual development of personality change and behavioural disturbance. Other: There are many other, less common, forms of dementia. |

Source: NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. May 2017 [iii]

This needs assessment

This is an assessment of the health needs related to dementia, with a focus on prevention and social care, in Wandsworth, designed with the aim of informing adult social care commissioning activities in the borough.

Within this aim, this document has four main objectives:

- To describe population need in relation to dementia, including the needs of those caring for people with dementia.

- To establish what preventative and social care services are available to meet this need

- To identify gaps in dementia care and preventative services.

- To recommend potential solutions based on best practice and population needs.

Dementia in the UK

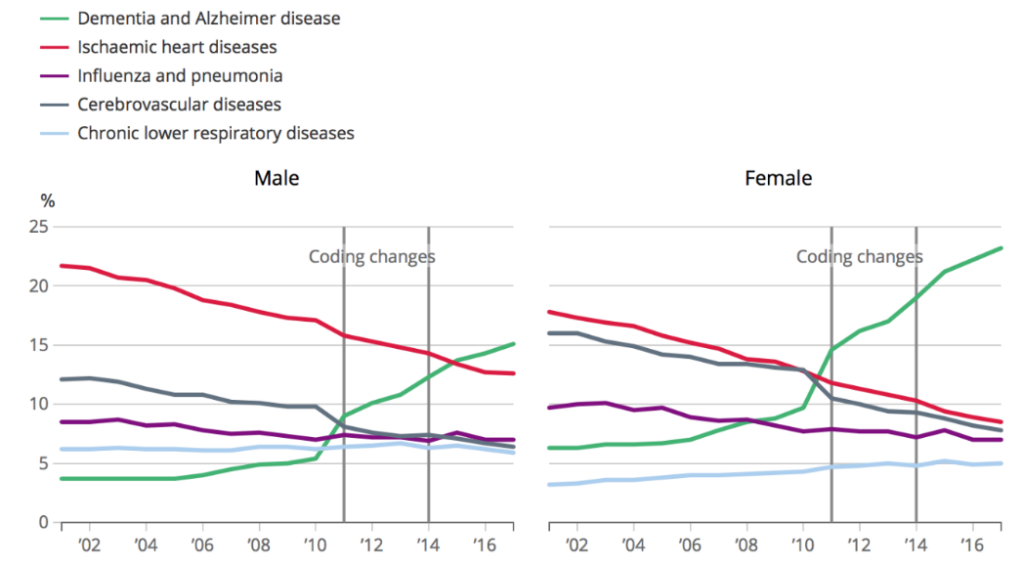

Dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, is now the leading cause of death in England and Wales, accounting for 12.7% of all registered deaths (see Figure 4). This is in the context of an anticipated increase in the number of people in the UK living with dementia, from 850,000 in 2018 to approximately 1 million by 2025 [iv].

Figure 4: Graphs describing the trend in proportion of deaths in England and Wales caused by the five leading causes of death in 2017 (2001-2017).

Source: ONS [v]

In acknowledgement of this growing impact, the ‘Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020’ (2015) was published. This described the need to improve recognition of dementia, quality of care and strength of community support. The value of ‘dementia friendly communities’ with strong local authority engagement in ‘Dementia Action Alliances’ was also emphasised [vi].

Subsequently, Public Health England (PHE) published a report on Dementia in 2018 highlighting the importance of local authorities’ role in reducing dementia risk through the promotion of healthy lifestyles and maximised use of signposting opportunities[vii]. Additionally, Pharmacy: A Way Forward for Public Health (2017) highlights the potential for local pharmacies to play an impactful role in improving the lives of people with dementia [viii].

The increasing need related to dementia, and disease prevention, nationally is also recognized in the NHS Long Term Plan (2019). The Long Term Plan builds on the Five Year Forward Plan, published in 2014, which included an ambition to offer “a consistent standard of support for patients newly diagnosed with dementia” [ix], [x].

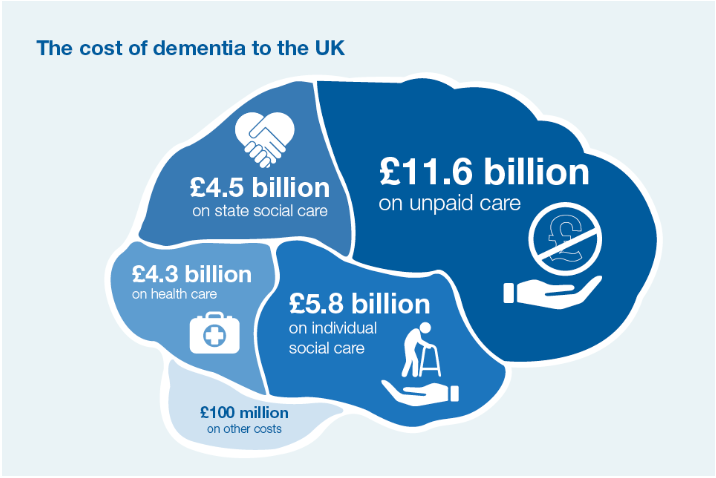

In addition to the need for support amongst those with dementia, there is an increasing appreciation of the need to support the growing community of informal carers[1]. Annually, the cost of dementia in the UK is estimated to be approximately £26 billion, £11.6 billion of which is attributable to unpaid care and £4.3 billion to healthcare (see Figure 5) [xi]. This indicates the size of the contribution made by informal carers to dementia care. In response to this, The Carers Action Plan 2018-2020 was published by the DoH. This builds on the 2014 Care Act to improve recognition of, and support for, informal carers [xii], [xiii].

Figure 5: The cost of dementia in the UK.

Source: Public Health England xi.

Dementia in Wandsworth policy

Although there is no strategy specifically designed to address dementia needs in Wandsworth, there are multiple strategies in which dementia and dementia-related care are considered (see Table 1).

Overall, the policy context in Wandsworth describes a recognition of people with dementia, and carers for people with dementia, in addition to acknowledging the need for improved service accessibility in the borough, whether that be access to medical care, housing or social activities.

Table 1: Summary of Wandsworth policy documents related to dementia.

| Document | Key points related to dementia | Year(s) |

| Wandsworth Local Health and Care Plan | – Aims to join up health and social care services

– Aims to increase awareness of dementia amongst frontline staff – Recognises increasing demand for home care services – Recognises the importance of preventative work – Commits to improve care navigation and support of unpaid carers |

2019-2021 |

| Wandsworth Health and Wellbeing Strategy | – Recognises dementia as one of the ‘biggest issues facing older people’.

– Commits to improving mental health and wellbeing through work with communities. |

2015-2020 |

| Wandsworth Strategy for Older People | – Commitments made to address the gap in access to primary care services between those in care homes and those living in private accommodation.

– Acknowledges that older people should be able to make informed decisions about accommodation options appropriate to their needs. – Commits to promote older people’s access to community services. – Commits to “undertake innovative projects to combat isolation and loneliness”. – Commits to “provide advice, support and advocacy to help people identify entitlement, make claims and appeal where necessary” in relation to finance.

|

2015-2020 |

| Wandsworth CCG Annual Report 2018/19 | -Recognised that growing challenges related to dementia

– Stated that Wandsworth CCG is working toward implementation of new NICE guidance for dementia care across all areas. |

2019 |

| Active Wandsworth Strategy | Describes objectives to:

– Offer specialist services for people with specific health conditions – Think differently about delivery activity provision for less-active older people. |

2017 |

| Cultural Strategy for Wandsworth | Defined the first strategic principle as:

– “All residents should be aware of local opportunities to participate in cultural activities to broaden their intellectual and creative horizons. Barriers to participation must be identified and lowered so that activities can include everyone” |

2009 |

Overview of dementia in Wandsworth

New cases of dementia

For those aged ≥ 65 registered with a GP in Wandsworth, 12.6 per 1000 are diagnosed with dementia each year. This is significantly higher than average in London (10.3 per 1000) and England (11.1 per 1000). However, approximately 24.8% of people with dementia remain undiagnosed in the borough, therefore diagnosis rate is not a true incidence rate xxxii.

Implications

As up to 30% of cases of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia are attributable to modifiable risk factors, this rate highlights the large potential for primary prevention to reduce dementia-related need in the borough iii. Additionally, in relation to this high number of new cases each year in Wandsworth, we have the opportunity to ensure that long term plans, including those related to end of life care, are instituted early.

Current cases of dementia

Amongst those aged under 65 on Wandsworth practice registers, dementia prevalence is 1.58 per 10,000. (n=58). This is significantly lower than prevalence in London (2.28 per 10,000) and England (3.41 per 10,000). Dementia affecting those under 65 years accounts for 3.3% of dementia cases in the borough.

Of those aged ≥ 65 in December 2018, amongst whom dementia is more prevalent, 1,676 people on Wandsworth GP practice registers (4.85% of the total Wandsworth population aged ≥65yrs ) had a diagnosis of dementia, a significantly higher proportion than average in London. This figure climbs to 2,124 (6.91% of those aged ≥65yrs ) when those with dementia living without a diagnosis are included in calculations (with GLA population estimates used as the denominator) xxiii, [xiv], xxxii.

In total, in 2017/18, there were 1,613 people with a recorded diagnosis of dementia living in Wandsworth, equating to 0.4% of the population registered with a GP. Although a lower proportion than in the rest of London (0.5%), this is a significant increase from 0.3% of the population in 2013/14 (n=1,164).

Based on the figures above, and average costs of care per person with dementia, the total cost of dementia in Wandsworth in 2019 will be approximately £70.4m, £27.3m of which being attributable to social care costs and £11.6m to healthcare costs. (based on 2012/13 prices).

Implications

Both those affected by early- and late- onset dementia represent an opportunity both for secondary prevention activity to slow disease progression and to provide care sufficient to improve quality of life.

End of life

The rate of mortality, for people aged ≥ 65 in Wandsworth, is 961 per 100,000 people, significantly higher than average in London (814 per 100,000 people). In 2017/18, 288 people with dementia died in Wandsworth.

Implications

At the end of life, people affected by dementia often have an impaired ability to comprehend their environment, in addition to having a reduced capacity for autonomy. Consequently, the palliative care needs of this cohort, required to achieve minimal distress and discomfort, can be significant and, based on this high rate, may be greater than average regionally in Wandsworth xlix.

Where are those with dementia living within the borough?

Geographic areas

The neighbourhood with the highest prevalence of dementia in the borough is Nightingale (1.5% of those on GP practice lists), which has the highest dementia prevalence of any other neighbourhood (MSOA) in London. However, the prevalence of dementia is as low as 0.2% in Wandsworth South, Wandsworth Common, Putney Town & Wandsworth Park, Clapham Junction & East Hill, Clapham Common West and Lavender Hill West & Little India [xv]. However, these discrepancies may be partially explained by variations in case finding success rather than true differences in prevalence.

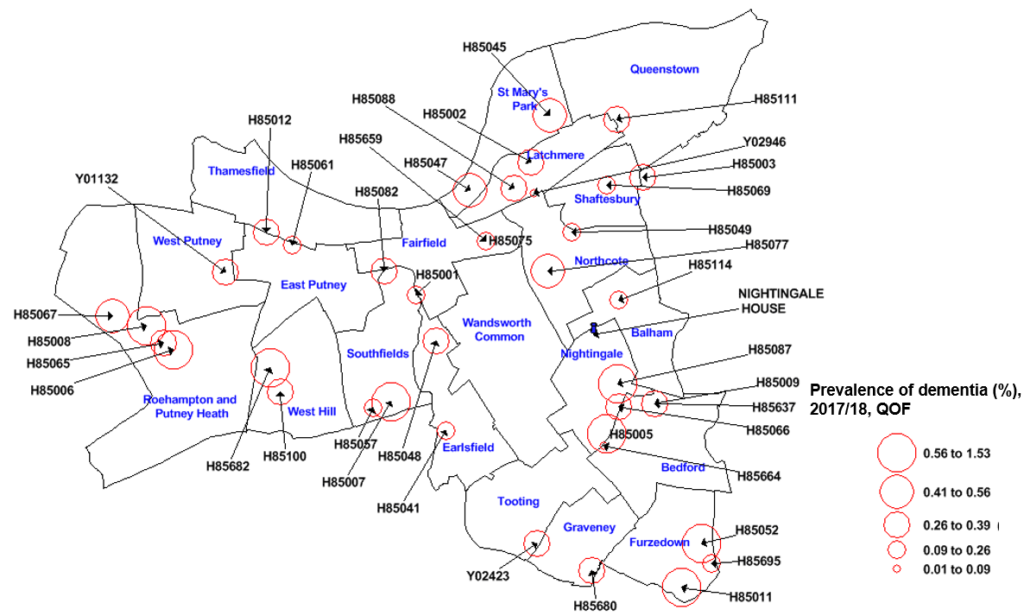

Figure 6, a map of diagnosed dementia prevalence by GP practice in Wandsworth, gives an indication of how dementia diagnoses are distributed within the borough. Whilst this distribution can act as a proxy to overall prevalence, true prevalence per practice will differ from that displayed, as practice diagnosis rates will vary, with some better at case finding than others. Furthermore, as practice size varies, the actual pattern of variation in the total number of people with a diagnosis of dementia per practice will differ from that shown below. Moreover, the location of large care homes may impact on local prevalence figures. Notwithstanding these limitations, the five practices with the highest prevalence are situated in the south and west of Wandsworth.

Figure 6:Prevalence of dementia in Wandsworth by GP practice, based on 2017-18 QOF data.

Source: QOF data

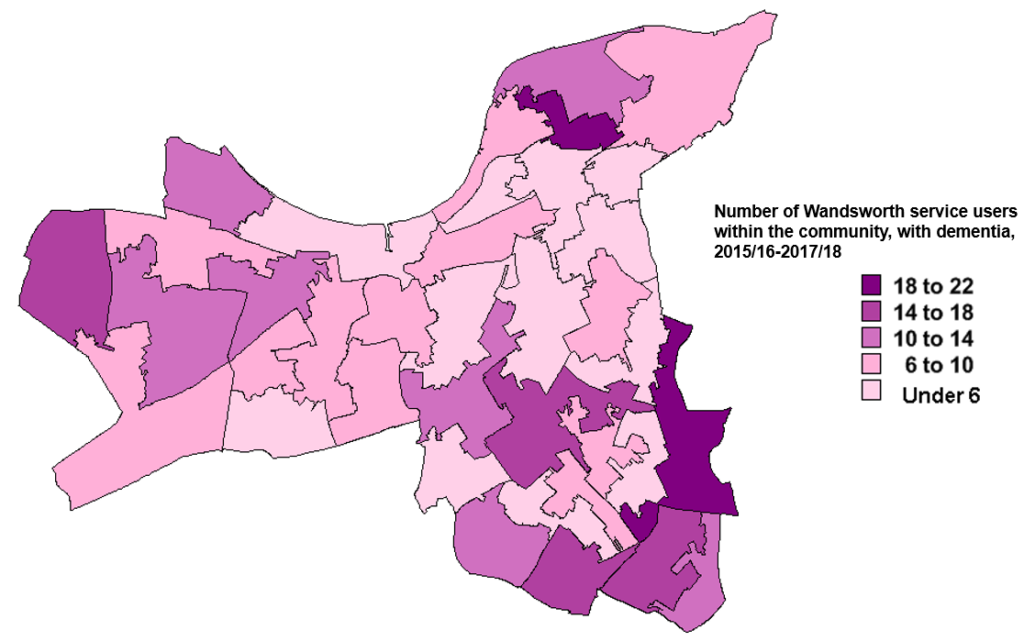

Figure 7 describes the distribution of ASC service users living with dementia in the community in Wandsworth over the past three years. It appears that a large number of those with dementia using ASC services from the community live in the south and west of the borough.

Figure 7: Map displaying distribution of adult social care service users living with dementia in the community in Wandsworth by MSOA between 2015/16-2017/18

Source: ASC data (Mosaic)

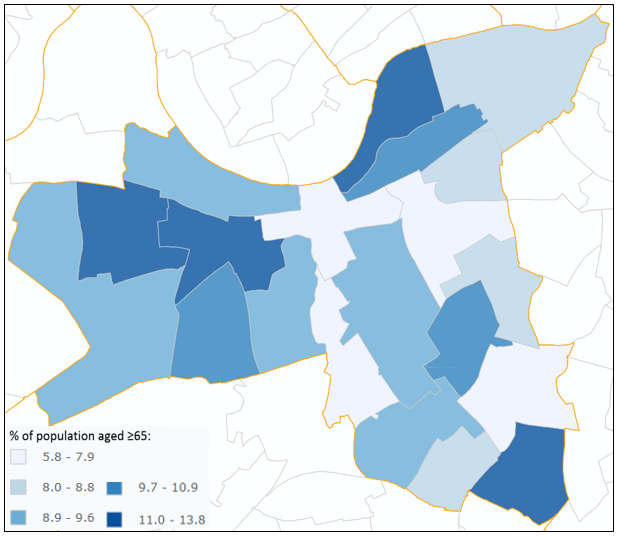

The areas with the highest proportion of people aged ≥65, i.e. those at the highest risk of dementia, are West Putney (13.8%), St Mary’s Park (12.7%) and East Putney (11.5%). This is in contrast to Northcote, where only 5.8% of the population are aged ≥65 (see Figure 8).

The size of this intra-borough variation, in both disease prevalence and risk factor prevalence, highlights the importance of considering geographic location when allocating resources related to dementia.

Figure 8: Map displaying the proportion of people aged ≥65 by ward in Wandsworth differentiated by quantile

Source: GLA London Ward Profiles (based on 2017 data).

Accommodation type

Based on estimates in the Dementia UK report, published in 2007, approximately 63.5% of people with late-onset dementia live in private households, with 36.5% living in care homes. In Wandsworth, this would equate to 1,349 people with dementia living in private homes and 776 people with dementia living in care homes [2] [xvi].

80% of local adult social care users with a diagnosis of dementia documented in Mosaic (a database of information relating to users of adult social care in the borough) lived in the community in 2017/18, as opposed to living in care homes, this is a reduction from 89% in 2016/17[xvii].

In 2017/18, of the 754 people receiving services under Wandsworth Adult Social Care (ASC) living in care homes, 6% had a diagnosis of dementia recorded on Mosaic xvii. This is dramatically lower than the typical proportion nationally, described in Table 2, suggesting that the degree of under-recognition and/or under-diagnosis in care homes in Wandsworth may be large.

Table 2 describes the estimated proportion of people resident in different accommodation settings who live with dementia [xviii]. Applying these proportions, to the numbers of people accessing ASC services as a denominator, we can estimate that 277 ASC service users living in residential accommodation have dementia, of a total of 479. For nursing homes, the equivalent figure is 201 of 275. Current ASC data counts only 18 people in residential accommodation and 27 people in nursing accommodation having a diagnosis of dementia xvii.

From this, it may be inferred that approximately 259 people accessing Wandsworth ASC services from residential homes, and 174 people accessing ASC services from nursing homes, are potentially living with a dementia that is unrecognised by the ASC team, and possibly not recognised at all. This suggests a need for either improved completeness of data collection, or for improved access to diagnostic services in care homes in the borough, or both.

Since 2015/16, the number of people with dementia recorded as such on Mosaic has increased threefold from 93 to 277. In addition to an increasing count, the proportion of all people using ASC services in Wandsworth, with a diagnosis of dementia recorded, has more than doubled from 3.0% to 6.8%. A proportional increase is observed in each care setting (community, residential and nursing). A nine-fold increase, the largest of any care setting, has been observed in nursing homes over this time (1.07% to 9.82%) xvii. Although this may be due to improved diagnostic rates in nursing homes, PHE data suggests that the overall CCG dementia diagnosis rate, as a proportion of total predicted cases of dementia, decreased between 2017 and 2018 xxxii. This suggests recording of dementia diagnoses on ACS databases is incomplete but improving.

Table 2: Table describing the estimated proportion of people within different care settings with dementia

| Care Setting | Female (%) | Male (%) | Total (%) |

| Residential homes | 62.1 | 52.7 | 57.9 |

| Nursing homes | 75.8 | 67.8 | 73.0 |

| EMI care homes | 90.6 | 86.7 | 90.1 |

Source: Figures extracted from Dementia UK: Second edition (2014) xviii.

Another important setting locally, beyond those described above, is Wandsworth Prison. Wandsworth prison currently holds 1,628 prisoners [xix]. Whilst a count of the number of people in Wandsworth prison living with dementia is not readily available, it is known that “older prisoners are the fastest growing group in the prison population, with an accelerated aging process they are at high risk of developing dementia” (Brook, Diaz-Gil and Jackson, 2018) [xx].

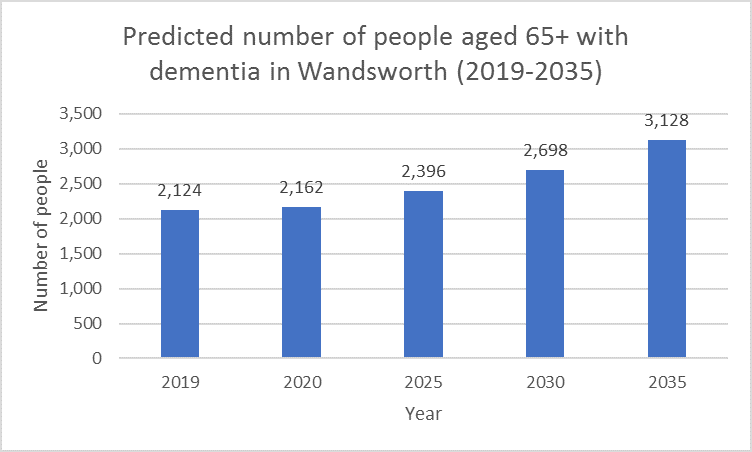

What does the future hold?

A 47% increase in the number of people aged ≥ 65 living with dementia is predicted in Wandsworth between 2019 and 2035 [xxi]. However, predictions for dementia incidence and mortality figures in the borough are not readily available.

Figure 9: Predicted number of people with dementia in Wandsworth (2019-2035)

Source: Adapted using IPC data

It is also anticipated that the number of people aged ≥ 65 living in care homes in Wandsworth will increase from 983 to 1,594 by 2035 xxi.

Based on the estimated increase in dementia prevalence suggested in Figure 9 , and assuming prevalence of early-onset dementia remains constant, we can estimate that dementia in Wandsworth in 2035 will cost approximately £102.7million in 2012/13 prices. The cost of social care alone will be approximately £40.1million.

What is driving this increasing prevalence of dementia?

The drivers of increasing dementia prevalence can largely[3] be divided into non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors. A modifiable risk factor is a behaviour or environmental exposure which increases disease risk but can be altered; whilst a non-modifiable risk factor is something that increases disease risk and cannot be altered.

Non-modifiable risk factors for dementia

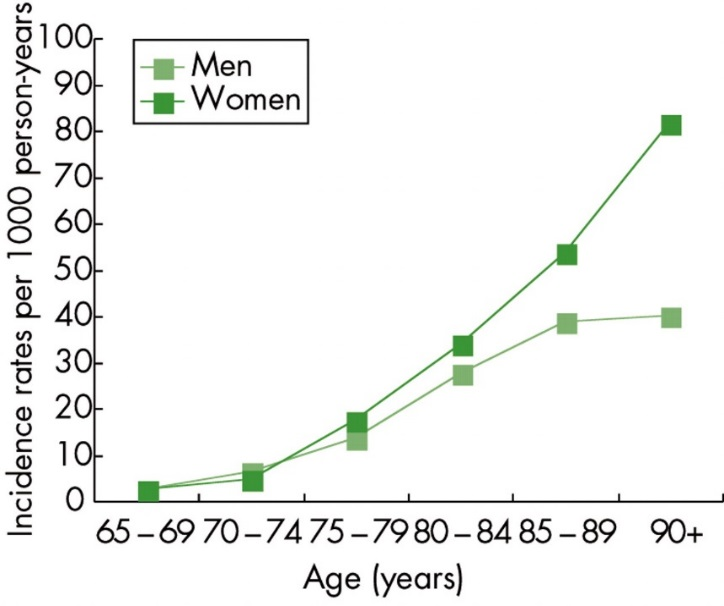

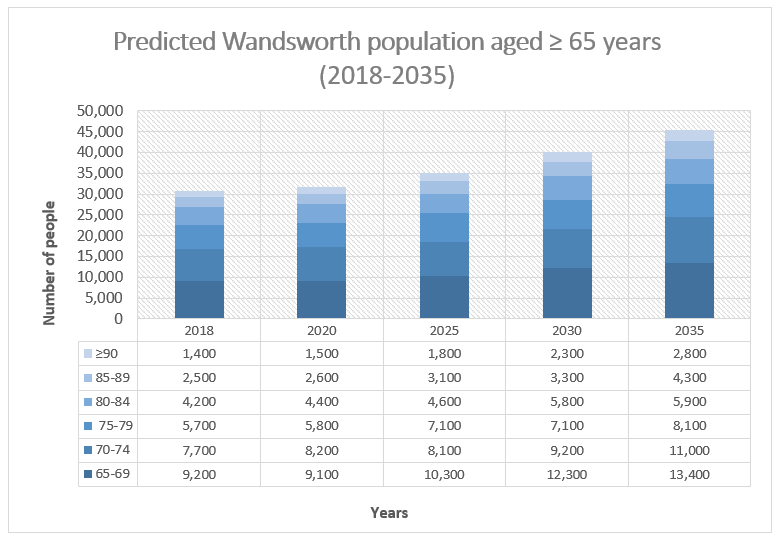

Age is the biggest risk factor for dementia, as the impact of stresses on the brain accumulates over time. Beyond the age of 65, risk of dementia approximately doubles every five years (see Figure 10) [xxii]. Of the 324,400 people currently thought to be living in Wandsworth, 9.5% are ≥ 65 years old (n= 30,744) [xxiii]. Between 2018 and 2050, the number of people aged ≥ 65 in Wandsworth is expected to increase by 87% to 57,622 (Figure 11 describes the predicted age distribution amongst those aged ≥ 65 in Wandsworth between 2018 and 2035) xxi.

Figure 10: Incidence of dementia according to age and sex.

Source: van der Flier WM and Scheltens P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2005. 76(5).

Figure 11: Predicted age distribution amongst those aged ≥65 in Wandsworth (2018-2035).

Source: Adapted from IPC data, informed by 2016 ONS data xxi.

Other non-modifiable risk factors include genetics, ethnicity and sex.

Most genetic risk factors are not routinely measured in the general population. Consequently, it is difficult to interpret the impact of genetics on risk locally. However, this may change as technology develops. Down’s syndrome, one genetic risk factor for dementia, is recorded more routinely. Prevalence of dementia amongst people with Down syndrome as young as 40-49 years is between 5.7-55%, this higher prevalence is partially attributable to increased amyloid deposition in the brain [xxiv] [xxv]. It is estimated that there are approximately 147 people affected by Down’s syndrome currently living in Wandsworth [xxvi]

Those affected by learning disabilities, other than Down’s syndrome, may also be at higher risk of dementia, although there remains uncertainty about how this risk is conferred [xxvii] According to QOF data, in 2016/17 there were 1,205 people, known to their GP, affected by a learning disability in Wandsworth.

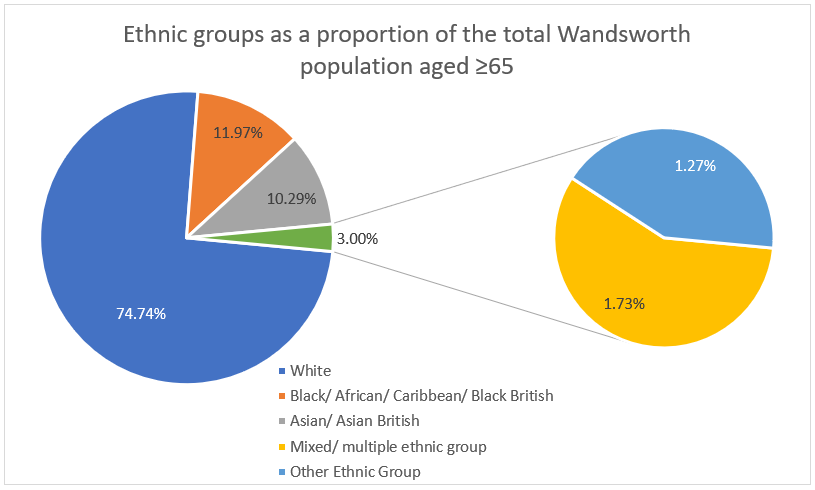

Certain ethnic groups are disproportionately affected by dementia, however the degree to which the environment and genetics are responsible for this difference is unclear. Whilst dementia prevalence in the UK is expected to double over the next 40 years, the prevalence of dementia amongst South Asian and Black ethnic groups will increase sevenfold xliv. This is relevant in Wandsworth as 25.26% of the population identify as Black, Asian and Mixed Ethnicity (BAME), based on the 2011 census (see Figure 12) [xxviii]. In 2016, 40.7% of people who died in Wandsworth, with dementia being identified as the underlying cause, were born outside of the UK. This could suggest that this difference in risk of dementia is manifesting in the borough[xxix].

Figure 12: Ethnic groups as a proportion of the total Wandsworth population aged ≥65

Source: Adapted using data from IPC, based on the 2011 census xxi.

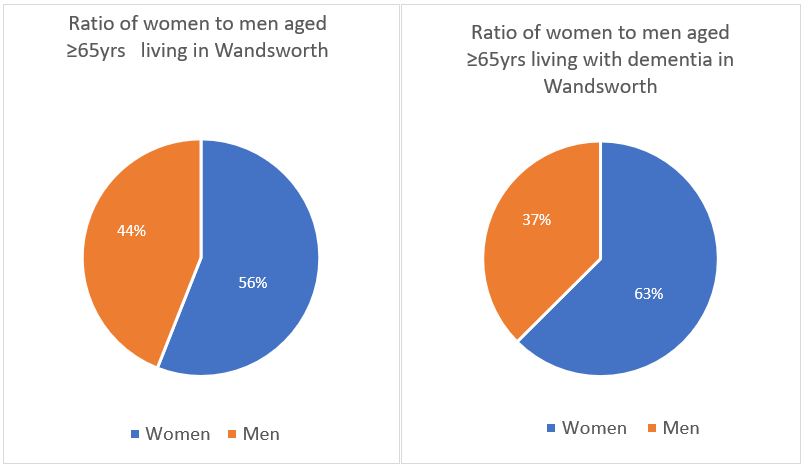

Women are at higher risk of late-onset dementia than men, however the underlying cause for this difference is uncertain. Currently 62.6% of those aged ≥65 living with dementia in Wandsworth are women (n=1,318), whilst 56% of the population aged ≥ 65 in Wandsworth are women (n=17,500) (see Figure 13) [xxx] xxi, xxviii.

Figure 13: Ratio of women to men aged ≥65yrs living in Wandsworth compared to ratio of women to men aged ≥65yrs living with dementia in Wandsworth.

Source: GLA population data and Institute of Public Care data xxx, xxi.

Modifiable risk factors

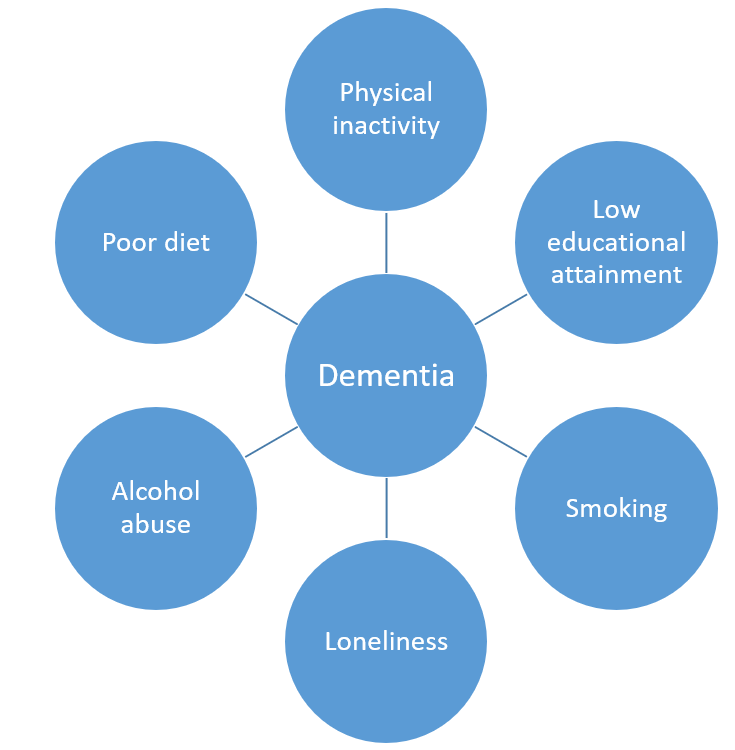

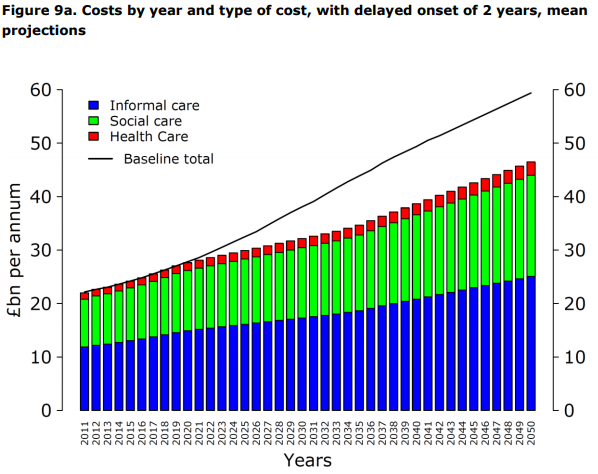

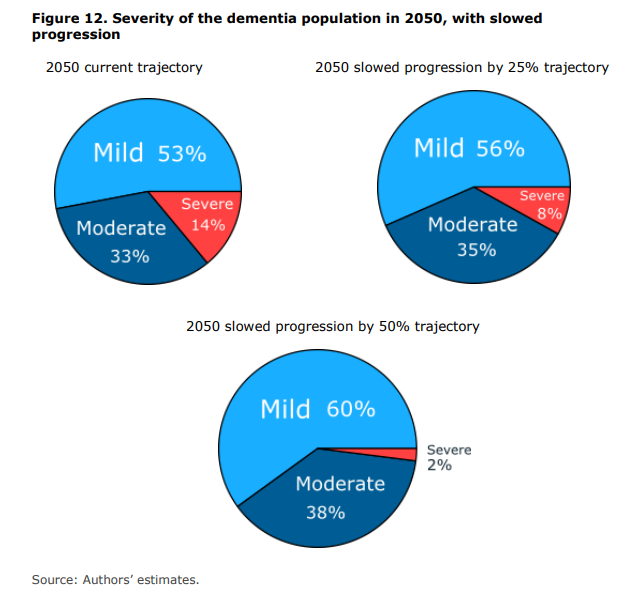

As stated above, up to 30% of the most common forms of dementia can be prevented. To achieve such a reduction in the number of people affected by dementia, modifiable risk factors need to be addressed before the onset of disease (see Figure 14). Delaying dementia onset, even by two years can achieve large savings related to health and care (see Figure 15). Even after a diagnosis of dementia, uptake of healthy behaviours can slow disease progression. The potential impact of slowed dementia progression rates by 2050 is shown in Figure 16 xi.

Figure 14: Modifiable risk factors for dementia

Source: PHE xi.

Figure 15: Mean projection of costs related to dementia, by year and type of cost, with delayed onset of 2 years compared to baseline cost predictions

Source: Lewis et al. Office of Health Economics and Alzheimer’s Research UK Error! Bookmark not defined..

Figure 16: Severity of the dementia population in 2050, with slowed progression.

Source: Lewis et al. Office of Health Economics and Alzheimer’s Research UK Error! Bookmark not defined..

Physical inactivity

The largest modifiable risk factor for dementia is physical inactivity. Even low intensity exercise, such as walking, can reduce an individual’s risk by around 40% [xxxi]. According to PHE, 18.4% of the Wandsworth population are ‘physically inactive’, lower than average in London (22.9%). Based on these figures, modelling suggests that approximately 9.8% (95% CI: 2.5% – 18.5%) of dementia cases in Wandsworth are attributable to physical inactivity [xxxii].

Low educational attainment

Low educational attainment follows on from inactivity, being attributable for around 7.2% (95% CI: 4.5%-13.3%) of dementia cases in the borough xxxi. This impact of early educational activity emphasises the importance of a life course approach in preventing dementia.

Smoking

As with many other health conditions, smoking is a major risk factor for dementia, with smokers having between 50-80% higher risk of dementia xxxi, [xxxiii]. Currently, adult smoking prevalence in Wandsworth is 13.4% (n=34,343), similar to average in London (14.6%)[4], xxxii. Modelling, based on these prevalence figures, suggests that 5.4% (95% CI: 1.5%-10.3%) of dementia cases in Wandsworth are attributable to smoking.

Loneliness and isolation

Another modifiable risk factor for dementia is loneliness. Both independently, and through its association with depression, loneliness increases dementia risk. One study suggests that older adults who feel lonely have 1.64 times higher odds of dementia compared to those who don’t feel lonely xxxi. It is estimated that only 42.2% of those using adult social care services in the borough feel they have as much social contact as they would like xxxii. The impact of loneliness on dementia in the borough may grow as the number of older people (aged ≥65) living alone in Wandsworth is expected to increase from 10,960 to 16,600 by 2035 xxi. The majority of those aged ≥ 65 living alone are female.

Alcohol

Alcohol, when consumed regularly in high volumes, can increase dementia risk. The number of hospital admission episodes for alcohol-specific conditions per 100,000 people in Wandsworth (655) is significantly higher than average in London (544) and England (570) and is increasing xxxii. This suggests that the pattern of alcohol consumption in the borough is conferring a higher risk of dementia on the population.

Air pollution

Additionally, there is increasing evidence that air pollution may contribute to dementia risk [xxxiv], [xxxv]. Wandsworth has been designated as an Air Quality Management Area since 2001 [xxxvi] .

Diseases associated with dementia

In addition to the modifiable behavioural risk factors above, there are also potentially modifiable disease processes related to dementia, many of which are related to the vascular risk associated with dementia. Table 3 describes the main diseases associated with an increased risk of dementia. As displayed in the fourth column, many risk factors for these conditions are the same as for dementia, further emphasizing the utility of promoting healthy behaviours in the borough.

Table 3: Description of diseases related to dementia and associated behavioural risk factors.

| Disease | Number of people affected in Wandsworth | Proportion of dementia cases attributable to disease (95% CI) | Modifiable behavioural risk factors associated with disease and dementia |

| High blood pressure[5] | 32,098 (QOF) | 3.6% (1% – 6.9%) | Diet, physical inactivity, smoking. |

| Depression | 21,884 | 3.1% (2.1%-4.4%) | Loneliness, physical inactivity, substance misuse, smoking, low educational attainment [6]. |

| Obesity | 17,340 (QOF) | 2.2% (1.3%-3.4%) | Diet, physical inactivity. |

| Diabetes | 14,460 (QOF) | 1.5% (0.6%-2.4%) | Diet, physical inactivity. |

| Stroke | N/A | N/A – dementia risk doubled amongst those who have had a stroke | Diet, physical inactivity, substance misuse, smoking. |

Source: PHE and NICE Error! Bookmark not defined., xxxi . [QOF = figure obtained from Quality and Outcomes Framework calculations].

Sensory impairment, both hearing and visual, can increase the care needs of people with dementia by reducing an individual’s ability to understand and navigate their environment. The number of older people affected by hearing loss and moderate or severe visual impairment in Wandsworth is expected to increase by 61.5% (from 2278 to 3678) and 53.6% (from 2,592 to 3982) respectively between 2017 and 2035.

Understanding of risk factors

A PHE survey in 2015 revealed that, whilst 59% of people know someone with dementia, 21% of the population could not identify any risk factors for dementia. Additionally, only 28% of people recognised smoking and 15% recognised high blood pressure as risk factors for dementia[xxxvii].

How is dementia risk being reduced in Wandsworth?

As discussed above, there are many different exposures that can increase dementia risk. Consequently, dementia prevention can be considered as any activity which actively reduces these risks, whether it is explicitly designed with a focus on dementia or not.

Below is an overview of local services related to dementia risk reduction.

Physical exercise

Enable leisure & culture are commissioned by Wandsworth Local Authority to provide a number of services to promote physical activity. These services function to support both primary and secondary prevention.

Within the ‘Active Lifestyles’ programme, provided within the Enable leisure & culture contract, a number of regular classes are run. Initial attendance at these services is free, however further participation is charged at a low price. Whilst some of these classes are targeted at those aged 50+, there are no services provided specifically for those with dementia.

Between October 2017 and September 2018, there were 8018 attendances within the ‘Active Lifestyles’ programme, with 680 participants in regular contact. Most participants were female (575 females, 105 males). Whilst it is difficult to comment on age and ethnic distribution as many participants did not specify these in the survey, approximately 25% of those that did were aged ≥65 and 45% were from BAME groups. The three wards with the greatest number of participants are: Roehampton and East Putney (n=93; 13.68%), Queenstown (n= 82; 12.06%) and Fairfield (n=66; 9.71%) [xxxviii].

There are other physical activity services provided by Enable leisure & culture beyond the ‘Active Lifestyles Programmes’ which are focused on groups at higher risk of dementia. These include: ‘Active Wellbeing’, a specialist exercise programme for adults with a severe mental health condition, and ‘Moving Forward after Stroke’, a 12-week programme of exercise and education for those who have had a stroke. In addition to these services, Enable leisure & culture facilitate walk for life events in Wandsworth[xxxix].

Park space is maintained by local authority commissioned services which facilitate independent exercise and social interaction.

Additionally, Slimming World and Weight Watchers deliver self-funded weight loss programmes locally.

Smoking cessation

Within the borough there are local authority commissioned smoking cessation services functioning in association with local primary care services. This is supplemented by support services for St George’s hospital related to smoke-free areas.

Isolation and loneliness work

In addition to the social opportunities related to the services above, Age UK Wandsworth provides a befriending service for older people in the borough.

Alcohol services

In Wandsworth, there is a community alcohol detoxification service, run through two GP practices, in Battersea and Putney called ‘Fresh Start Clinics’.

There are also services providing abstinent and non-abstinent day programmes for drug and alcohol service users, including those returning from Residential Rehabilitation.

The Local Authority, in conjunction with Wandsworth CCG, commission a Drug and Alcohol Liaison Team within St George’s Hospital to offer treatment within the hospital and to liaise with community services to move as many patients that would like help with their alcohol or drug issues into treatment as smoothly as possible.

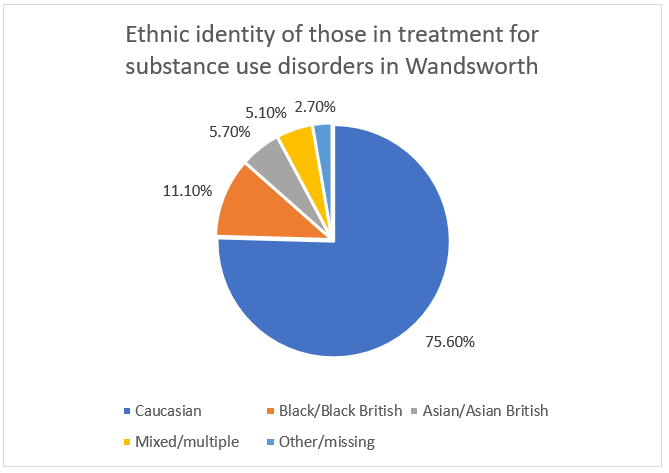

Of the 1502 Wandsworth residents in treatment for alcohol and substance use disorders, 8.1% were aged ≥65yrs. The ethnic identity of those in treatment is described in Figure 17.

Figure 17: Ethnic identity of those in treatment for substance misuse in Wandsworth.

Source: NDTMS 2018

Recognition and treatment of medical conditions related to dementia

Whilst it is beyond the scope of this needs assessment to comment on the available treatments for all medical conditions related to dementia risk, it is important to note that Wandsworth continues to provide NHS Health Checks which support recognition of these conditions, in addition to screening for dementia itself. These are free to access for those between 40 and 74 years old.

Following diagnosis, how are those with dementia cared for in Wandsworth?

Post-diagnostic support

Following a diagnosis of dementia, collaborative care planning is typically commenced within the memory assessment services provided by SWLStG mental health trust. This service supports with accommodation planning, medication reviews, exploring the interests of people with dementia and reviewing carers needs[7]. These care plans are not currently routinely shared with GPs.

Following collaborative care planning, people in Wandsworth are often referred to the local Alzheimer’s Society team, who provide support services.

‘Life after diagnosis’, a programme provided by the Memory Assessment Service, is a 4-week programme with peer involvement intended to facilitate communication and co-support between people recently diagnosed with dementia.

This service is supplemented by the Carers Dementia Awareness Training, run via the Wandsworth Carers’ Centre. This is a 3-week course which aims to provide carers with the information about dementia required to most effectively support somebody living with dementia.

The themes of support in these sessions include information about dementia, advice on important actions in the context of dementia, such as how to establish a lasting power of attorney, and guidance on what other services are available in the borough.

More unstructured support is provided by the borough in the form of cafés, reminiscence workshops, dementia support groups and carer support groups. These are environments where people affected by dementia are able to develop social support networks (Table 4 describes a list of services provided locally).

Other services in the borough are provided by the Alzheimer’s Society, who provided for 1188 unique service users in 2017/18. This is supplemented by 2.5 days per week of dementia support in St George’s hospital. This number is likely to decrease following the end of the Carers Partnership Wandsworth contract with the Alzheimer’s society.

Table 4: Table describing dementia services provided in Wandsworth.

| Service | Description of service |

| Dementia support workers | Provide personalized support for families affected by dementia. |

| Dementia advisor service | Offer tailored information and support to people with dementia and carers for people with dementia. |

| Carers’ peer support groups | Support carers for people with dementia and facilitate construction of carer networks. |

| Peer support group (Little Grey Cells) | Facilitate peer support between people in the early stages of dementia |

| Early-onset dementia support group | A support group, based in St George’s hospital, specifically for people with early onset dementia. |

| Dementia Cafés | Once monthly dementia cafes provide access to a location for social interaction and informal peer support, in addition to providing information. |

| ‘Singing for the Brain’ | An evidence-based singing session for those affected by dementia intended to increase brain stimulation provided on a weekly basis |

| Carers Dementia Awareness Training | A 3-week course aiming to equip carers with the necessary skills and information to support somebody living with dementia. |

| ‘Life after Diagnosis’ | 4-week programme designed to foster peer support and provide information related to dementia. |

| Wandsworth Prison services | 1 day per week of dementia support/information/awareness raising in Wandsworth prison. |

Social care after diagnosis

As described above, most people affected by dementia live in private accommodation. Many of those with mild dementia will live independently in this context. However, for people living in private accommodation who are not independent, their care will come from informal sources, formal ‘home care’ provision and day-centre services.

Although not specific to dementia, it is estimated that in 2018, 1,790 people aged ≥ 65

provided ≥20 hours of unpaid care per week in Wandsworth, this figure is expected to increase to 2,591 by 2035 xxi.

This is in comparison to 1,290 adults receiving ‘home care’ on 31st March 2013. In addition to being less than informal care provision locally, this is less ‘home care’ provision than is provided on average regionally and nationally, proportional to population size xxxii. A more recent review counts 1,994 service users in Wandsworth receiving home care and describes increasing demand for this service in the Borough [xl]

In 2013/14, 570 people attended day care services, not specific to dementia, in the borough. This equated to 225.9 per 100,000 people. Wandsworth currently has one day centre catering for those with dementia, Holybourne Day Centre. Holybourne Day Centre is located in Roehampton and has 225 places over 7 days. The centre is open daily from 8.00-6.30pm and includes lunch and dinner provision. There is limited access via public transport, however a bus service is provided by the centre. Day rehabilitation services are also available at Brysson White Day Hospital, attached to Queen Mary Hospital.

This suggests that, overall, support for those with dementia living in private accommodation is comparatively limited in supply compared to the rest of London and England. Although there are other services, such as dementia cafes and peer support groups for people with dementia and informal carers, this lack of available day services for people living with dementia is likely to contribute to informal care supply being overstretched and potentially contribute to an increase in need for care homes and hospital admissions.

In the later stages of dementia, care homes are often required to provide the support needed to maintain a good quality of life and reduce risk of harm. Wandsworth has 1132 care home beds designed to support people aged ≥ 65. This equates to 3,712.9 care home beds per 100,000 people aged ≥65. This is a high proportion of the 1,253 care beds in total in the borough [xli]. In total, there are 22 care homes catering for older people in Wandsworth.

PHE calculate that, for every 100 people with a registered diagnosis of dementia in Wandsworth, there are 75.5 care beds. This is a significantly higher proportion than average in the rest of London (51.3 per 100) and England (69.2 per 100).

Although care bed supply is comparatively high in the borough, the proportion of care beds rated as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by the CQC in Wandsworth (51.7%, n=551) is significantly lower than average in London (61.4%) and England (59.7%). The proportion of care homes requiring improvement was the highest in South West London in June 2018 xli.

In addition to low quality of care threatening to limit quality of life of care home residents, it is also likely to increase risk of hospital admission and potentially increase the rate of functional decline.

The medical and social care interface

Whilst this needs assessment is not designed to comment on in-hospital dementia care, some hospital metrics can provide an insight into care quality in the community.

Emergency admissions

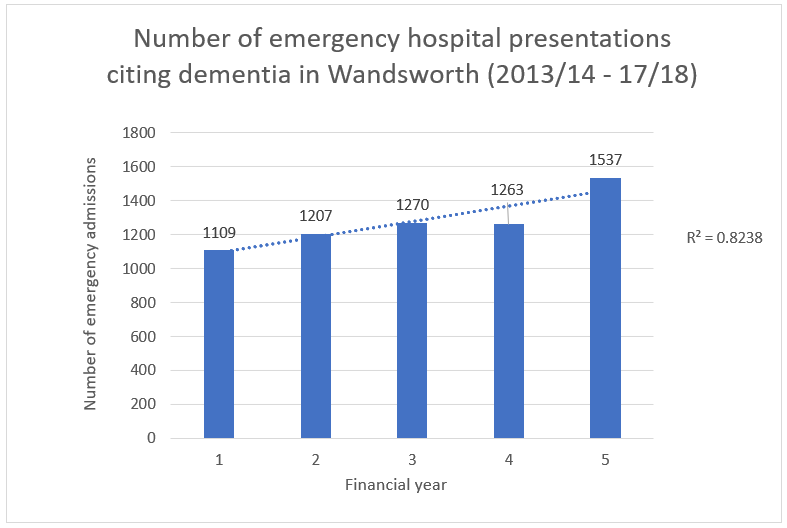

The directly standardised annual rate of emergency admissions to hospital for those aged ≥65 with dementia in Wandsworth in 2016/17 was 4,299 per 100,000 people[8] (n=1,263). This is significantly higher than average in London (4,052 per 100,000) and England (3,482 per 100,000) and there is a significant increasing trend in emergency admissions (see Figure 18). Rather than being the primary reason for emergency admissions, dementia is most often a secondary or tertiary diagnosis in Wandsworth, emphasizing dementia’s relationship to comorbidities [xlii]. Whilst the trend seen in Figure 18 shows a statistically significant positive association between time and emergency admissions, it is not causative. There are many possible underlying causes which may be responsible for the increasing trend in dementia related emergency admissions, including increased dementia prevalence, reduced quality of formal dementia care and/or reduced informal care capacity, amongst others.

Figure 18: Number of emergency hospital presentations citing dementia in diagnostic coding amongst Wandsworth residents between 2013/14 and 2017/18.

Source: Figures derived from Hospital Episode Statistics. NHS. [p=0.03; p value relates to two-way significance of positive trend based on linear regression]. 1 = 2013/14, 2= 2014/15, 3 = 2015/16, 4 = 2016/17 and 5 = 2017/18.

One finding, suggesting inadequate care quality may be responsible for this trend, is that Wandsworth has the highest ratio of LAS call outs and conveyances to hospital, relative to the number of care beds, in South West London (1.06:1 and 0.92:1 respectively). This is consistent with CQC findings that multiple care homes in Wandsworth provide an inadequate quality of care xli. The highest ratio of both call-outs and conveyances to care beds, for any care home in South West London was attributed to Brendoncare Ronald Gibson House. For each care bed in Brendoncare Ronald Gibson House, there are an average of 2.9 LAS callouts and 2.5 conveyances to hospital each year.

However, the proportion of emergency admissions lasting ≤1 day (30.5%) is similar to average in London (28.9%). This suggests that the extent of illness on presentation to hospital may not be significantly different to average in London.

Dementia Sub-type

Interpreting demand for hospital services according to dementia sub-type is challenging as the most common presenting primary diagnosis related to dementia is ‘unspecified dementia’, and coding of late vs. early onset is sparse. However, 57% of those admitted as an emergency to hospital from Wandsworth with a primary diagnosis related to dementia, other than ‘unspecified dementia’, were admitted with a form of Alzheimer’s disease[9] and 41% with vascular dementia xlix. This is similar to national dementia sub-type ratios iii.

Discharge

Following discharge from hospital, there is often a brief period of increased need for support whilst people readjust to their home environment. In response to this, 3.4% of those aged ≥ 65 in Wandsworth receive reablement following discharge (n=130). This is a significantly lower proportion than average in London (5.0%). However, 91 days after discharge, 92.3% of Wandsworth residents aged ≥ 65 remain at home. This is similar to average in London (88.1%), suggesting that the quality of post-discharge support may be sufficient. However, this data is from 2013/14 and the current picture may be different.

Community clinical services

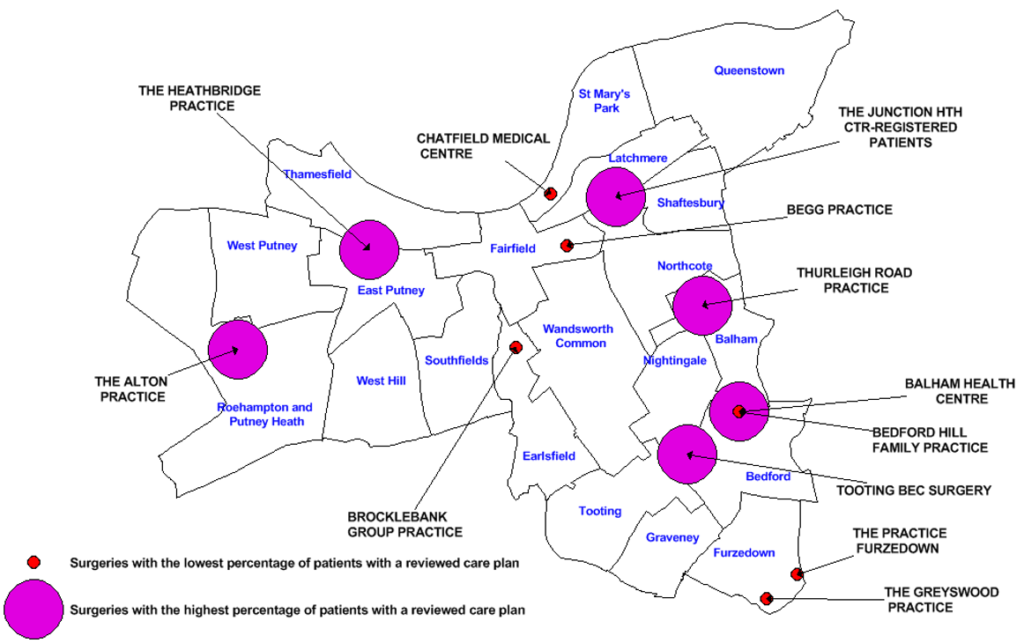

As part of the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), GPs are incentivised to complete a face-to-face annual review of care plans for people living with dementia. The range of achievement for this QOF in the borough is wide, with Balham Health Centre, Tooting Bec Surgery and The Junction Health Centre achieving 100% completion in 2017/18 and Thurleigh Road, The Heathbridge and The Alton Practices all achieving >90% completion. In contrast, Begg practice and The Practice Furzedown achieved 66.7% completion. Figure 19 describes the geographical distribution of the high, and low, performing GP practices in the borough. This indicates that many of the borough’s lowest performing practices are in south and central Wandsworth.

Figure 19: Map describing the distribution of the six Wandsworth practices with the highest, and the six with the lowest, proportion of annual dementia care plan reviews completed in 2017/18.

Source: QOF data

Additionally, there are dementia clinical nurse specialists employed in the borough, at a primary care level, to recognise medical and care issues early and support with the management of comorbidities.

Another NHS service, designed to avoid admissions, is the Behaviour and Communication Support Service. This service supports care homes to reduce dependency on antipsychotic medications and navigate care in the context of behavioural and psychological symptoms associated with dementia-related distress.

End of life care

Dementia is a life-limiting condition and, as stated above, the leading cause of death nationally.

Synergy between social and medical care towards the end of life is crucial. In order to achieve adequate comfort in one’s final days, enhanced and coordinated support is often required. The extent to which we successfully support residents experience a positive end of life is difficult to measure as each individual will have different needs. In Wandsworth in 2016, 66.2% of people with dementia died in their usual place of residence, one metric of palliative care quality; this is higher than average in London (55.8%). Although, similar to average in London (13.2%), only 15.3% of people with dementia died at home. These metrics do not differentiate between successful community care that maximises time at home from prolonged inpatient admissions secondary to poor palliative care. Therefore, these figures should be interpreted with caution.

A tool increasingly used nationwide to improve end of life care is ‘coordinate my care’ (CMC). This is an IT resource on which the needs and wishes of people with various medical conditions are logged. 91% of those who have a CMC record in Wandsworth have their preferences related to death recorded (i.e. preferred place of death). However, only 32% of people living in Wandsworth care homes have a CMC record xli.

Much of the palliative care in Wandsworth is provided by Royal Trinity Hospice (RTH). The RTH community team, which provide much of the palliative care for people with dementia, consists of three registered nurses who visit people in their place of residence.

In addition to this, the hospice hosts an event, known as ‘Monday club’, once weekly. This provides activities in-house and enables carer respite. For those with dementia, a befriending service is also available through the hospice.

Within the hospice building there is a dementia friendly bay and staff are trained as dementia friends.

Carer support

In 2016/17, carer-reported quality of life scores for people caring for someone with dementia was significantly lower in Wandsworth than average in London and England based on an ASCOF survey.

Additionally, only 25.1% of adult carers in Wandsworth have as much social contact as they would like. This figure significantly decreased between 2014/15 and 2016/17 and is significantly worse than average in London (35.6%) and England (35.5%).

As described in Table 4, there are services in the borough available for carers of people with dementia, however, based on the figures above, these services may be insufficient and/or inaccessible for many carers in the borough. As there was no capacity to seek the perspective of carers in Wandsworth in this needs assessment it is difficult to determine which limitation is greater.

Equity of access

As dementia risk is inequitably distributed in society, the need to proactively address equity in access to prevention and care services is paramount. Whilst the following section aims to review how we are promoting equity, current data on Adult Social Care use for specific services in relation to demographic features for those living with dementia is limited. Hence, much of the findings described below should be interpreted with caution.

Table 5 summarises the services in the borough designed to support specific groups.

Table 5: Table listing services in Wandsworth with a focus on particular cohorts of people affected by dementia

| Protected characteristic | Service | Description | Location |

| Sexual Orientation | The Proud Carers | A support group located in Balham designed to support carers for people with dementia who identify as LGBTQI. | Balham |

| The Furzedown project | Amongst other services, the Furzedown project provide a coffee morning for those identifying as LGBTQI. | Streatham | |

| Age | Early Onset Dementia Support Group | A service providing general support for people affected by early onset dementia | Tooting |

| Religious beliefs | Yahweh Christian Fellowship | ‘Dementia project’ designed to support people with dementia and their friends and family. | Tooting |

| Ethnicity

Sex |

Lambeth Chinese Community Association | Provides a range of services, not necessarily specific to dementia, including carer support, befriending and advocacy. | Lambeth |

| Bhakti Shyama Care Centre | Provides services dedicated to the spiritual needs of Guajarati residents. (Capacity = 25). | Balham | |

| Wandsworth Carers’ Centre | Provides targeted support for Asian Carers | Southfields | |

| Men’s Shed | Facilitates social activities for older men, although not specific to dementia | Roehampton |

In relation to the use of adult social care in Wandsworth by ethnic group, 64% of service users identify as White, 12% identify as Asian/Asian British and 22% identify as Black/Black British in 2017/18 xvii.

Between 2013/14 and 2017/18, 67.2% of emergency dementia-related admissions to hospital were for people identifying as Caucasian, whilst the 2011 census described 74.45% of the Wandsworth population identifying as Caucasian. This discrepancy may be attributable to changing demographics or a disproportionate demand for emergency care amongst BAME populations affected by dementia xlix. Of those with a dementia diagnosis in January 2019 in Wandsworth; 259 identified as White, 154 identified as Asian or Asian British, 49 identified as having mixed/multiple ethnic background and 19 identified themselves as a member of another ethnic group. This suggests a highly disproportionate representation of people from ethnic minorities amongst those with a diagnosis of dementia in Wandsworth. However, 73% of people with a diagnosis of dementia in the borough do not have their ethnicity recorded. Consequently, whilst these figures may rationalize further investigation, they should be acted on with extreme caution[xliii].

Although not related to Wandsworth specifically, there is parity of access to memory clinics between Caucasian and BME communities in London overall [xliv].

Another important domain to consider in relation to dementia is sexual orientation as it is well described that the needs of people identifying as LGBTQI can vary from those identifying as heterosexual [xlv]. In London in 2017, 89.8% of people identified as heterosexual,2% identified as gay or lesbian, 0.6% identified as bisexual and 0.6% identified as ‘other’ [xlvi]. Data on the sexual identity of Wandsworth adult social care users with dementia is only available for 21.6% of this cohort for 2017/18.

As described above, the risk of dementia is higher for women than for men. This is observed in Wandsworth as there are 1.6 times more women with dementia accessing adult social care services than men with dementia (2017/18). However, this ratio has reduced from double the number of women accessing services than men in 2015/16. This change in ratio could mean that women’s risk factors for dementia have been reduced to a greater extent than men’s, or that services are becoming more accessible to men, or that men are not dying when receiving care as often as previously, amongst other potential causes.

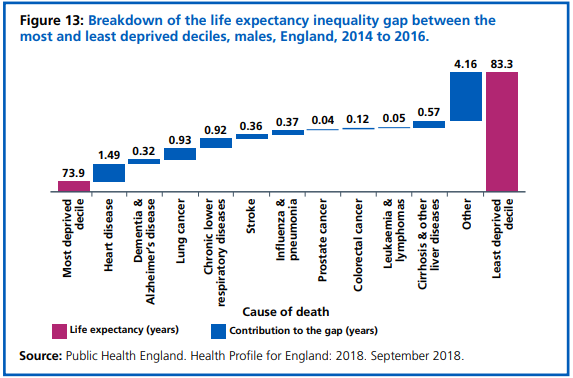

Dementia contributes to the inequity in health between most and least deprived social groups (see Figure 20). However, the data to establish if this inequity is addressed through service provision in Wandsworth is not presently available.

Figure 20: Graph depicting the breakdown of the life expectancy inequality gap between the most and least deprived deciles for males in England (2014-2016).

Source: NHS Long Term Plan ix.

How does dementia prevention and care in Wandsworth compare to national guidelines?

Prevention

In 2015 NICE guideline 16 was published, ‘Dementia, disability and frailty in later life – mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset’ (Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng16 ) [xlvii]. The aims of this document are threefold: to reduce modifiable risk factors, to reduce incidence of related non-communicable diseases and to increase resilience through promoting social and emotional wellbeing.

The recommendations within NICE guideline 16, to encourage and facilitate healthy behaviours, are described in Table 6.

Table 6: Table describing NICE guidance 16 recommendations, actions and service gaps relevant to local authority activity.

| Recommendation | Action | Gap(s) in Wandsworth |

| Encouraging healthy behaviours | Develop and support population level initiatives. | No initiatives explicitly related to lowering dementia risk. |

| Integrating dementia risk reduction prevention policies | Incorporate dementia into other health-related policy documents. | Limited reference to dementia risk factors in WLA policy documents. |

| Raising awareness of risk of dementia, disability and frailty | Commission local campaigns to show how dementia risk can be reduced, even in earlier life | No local campaigns to increase awareness of dementia and related risk factors beyond that achieved via NHS Health Checks. |

| Producing information on reducing the risks of dementia, disability and frailty | Provide advice on risk reduction activities, such as smoking cessation and diet improvement. | Smoking cessation and diet improvement resources available, however limited reference to dementia risk. |

| Preventing tobacco use | Extend smoke-free areas and continue commissioning smoking cessation services. | Smoking cessation services available with ‘smoke-free area’ support existing for NHS services |

| Improving the environment to promote physical activity | Use traffic management and new developments to encourage active travel. | No current activity related to the ‘healthy street’ approach. |

| Reducing alcohol-related risk | Utilise early morning restriction orders and cumulative impact policy as necessary to influence licensing. | There is no active cumulative impact policy in Wandsworth. |

| Supporting people to eat healthily | Limiting the number of unhealthy food outlets and improving access to healthy food. | Food licensing strategy active to limit proximity of unhealthy food outlets to schools but limited in other strategies. |

Care

For those who have developed dementia, and for carers of people with dementia, NICE guideline 97, framed around the principles of person-centred care in the context of dementia, was published in 2018 [xlviii]. The recommendations most relevant to local authority activity are described in Table 7 xlviii:

Table 7: Table describing NICE guideline 97 recommendations, actions and service gaps, in relation to local authority activity.

| Recommendation | Action(s) | Gap(s) in Wandsworth |

| Involving people with dementia in decisions about their care | – Provide relevant and accessible information and encourage involvement in decision making.

– Offer early and ongoing opportunities for involvement in advanced decision making. |

– Many carers feel insufficiently involved in decision making in Wandsworth xxxii. However, there is limited evidence regarding the extent of involvement of people with dementia in decision making.

|

| Care coordination | – Provide people living with dementia with a single named health or social care professional who is responsible for coordinating their care who should be involved in developing a care and support plan [10].

– Ensure information can be easily transferred between care settings. – Design services to be accessible as possible |

– Structurally fragmented care provision. Dementia advisors available but increasingly overstretched and don’t provide a complete ‘co-ordination’ role. |

| Interventions to promote cognition, independence and wellbeing | – Offer a range of activities to promote wellbeing which can be tailored to an individual’s needs, including group cognitive stimulation therapy.

– Consider offering cognitive rehabilitation, occupational therapy and group reminiscence therapy. |

– limited formalized availability of regular cognitive stimulation therapy and other evidence-based activities. |

| Assessing and managing other long-term conditions | – Ensure that people living with dementia have equivalent access to diagnosis, treatment and care services for comorbidities as those who do not have dementia. | – Inconsistent primary care provision within care homes.

Although, there are dementia specialist nurses available in the borough to support in recognition of mismanaged comorbidities. |

| Palliative care | – For people living with dementia who are approaching the end of life, use an anticipatory healthcare planning process involving the person, their carers and their family.

– Support eating and drinking and consider involvement of speech and language therapy. |

– Limited completion of advanced directives [xlix]

– Limited utility of tools to coordinate EOL care, such as CMC; the aim is to address this in 2019 via additional input within the Enhanced Health in Care programme xli |

| Supporting carers | – Offer carers for people living with dementia psychoeducation and skills training intervention.

-Ensure that support provided to carers is personalized, accessible and available after diagnosis and beyond. |

– Whilst services do exist, the data suggests that the support is insufficient or inaccessible

– psychoeducation provision is not formalized.

|

| Moving to different care settings | – “Review the person’s needs and wishes (including any care and support plans and advance care and support plans) after every transition.” | – Minimal evidence of formal consideration of advanced decision making at points of care transfer. |

| Staff training

|

– “Care and support providers should provide all staff with training in person-centred and outcome-focused care for people living with dementia.” | – Lack of clarity regarding proportion of frontline staff that have received appropriate dementia training. Particularly in relation to advanced decisions making. |

Recommendations

Prevention

- WLA and Wandsworth CCG to consider including reference to dementia risk in future local prevention frameworks and any updated strategies related to exercise, education, smoking, alcohol consumption and isolation.

- WLA to utilise current local alcohol services, smoking cessation services and exercise/leisure services, where contractually possible, to communicate the beneficial impact of making positive lifestyle changes on dementia risk.

- WLA to work with SWL STP and Wandsworth CCG to create a consistent and coordinated multi-agency communication strategy to improve awareness of dementia risk in the borough. This may be based on the national campaign ‘what’s good for your heart is good for your brain’ [l].

- Use resources available within Making Every Contact Count work to increase frontline workforce awareness of dementia and the potential for prevention.

- Recognising increased risk of dementia within the BAME community, WLA should consider auditing preventative service use to ensure needs are being met equitably. Additionally, proactive methods to increase awareness of the value of preventative activities in these communities should be considered.

- Appreciating the positive impact of exercise on dementia risk, we should review how we can transform physical infrastructure in the borough to promote active travel, potentially in accordance with the ‘ ‘Healthy Streets’ initiative [li].

- WLA should consider formally reviewing activities provided, by day services, day centres and care homes in the borough for those with dementia, to recognize and/or support adherence to national evidence-based guidance and/or support e.g. cognitive stimulation therapy and group reminiscence therapy

Care

Coordination of care

- In response to the challenges some residents face in navigating local services, WLA and the CCG could consider, in collaboration, the potential to establish a named and accountable care coordinator, such as that described in a recent NICE report [lii].

- An additional activity the council can consider, in relation to service navigability, is to create a single point of access to information about local dementia services, this could make use of the ‘Dementia – Getting help in Wandsworth’

- Acknowledging the lack of standardised access to post-diagnostic services following diagnosis outside of the memory assessment services, Wandsworth CCG, SWL STP and SWLSTG MHT could consider reviewing current referral pathways.

- WLA could take lead in establishing a local Dementia Action Alliance to permit collaborative work to improve the lives of people with dementia through both public and private sector action locally [liii].

- To support in the coordination of end of life care, WLA and Wandsworth CCG should consider collaboratively creating a standardised document, capturing needs, wishes and advanced decisions of those affected by dementia to use when care is transferred between organisations.

- Due to inconsistencies in access to primary care for those with dementia living in local care homes, WLA and Wandsworth CCG should consider reviewing the potential for standardizing primary care accessibility for this cohort. Additionally, efforts should be made to standardise the quality of primary care provided to those living in private accommodation.

- SWLSTG Mental Health Trust could consider standardizing the distribution of dementia ‘collaborative care plans’ to GPs (and potentially other frontline professionals) in the borough.

Quality of care and support.

- WLA and Wandsworth CCG could collaboratively work to ensure recognition of dementia in local care homes is optimized and recorded effectively when recognised.

- WLA could consider leading the development of local communities into dementia friendly communities to reduce isolation and improve community engagement possibilities for those affected by dementia [liv].

- In response to incomplete data on the ethnicity and sexual orientation adult social service recipients, and the limits this places on measuring equity of service distribution, WLA could consider auditing current data collection methods and sharing any learning. Once the nature of dementia-related inequity is better understood in the borough, informed action to promote equity can be taken.

- Recognising the anticipated increase in sensory impairments in Wandsworth, and the potential for these to exacerbate dementia, WLA and Wandsworth CCG could consider reviewing the need to standardize access to screening services, where appropriate, within local day centres and care homes

- Due to limited information on current dementia training in the borough; WLA, Wandsworth CCG and South West London and St George’s Mental Health Trust could consider an audit of the proportion of frontline care professionals who have completed NICE recognized dementia awareness training.

- Consider increasing availability and flexibility of respite care, including day care centres, and home care support to facilitate carer wellbeing, reduce avoidable admissions and reduce isolation (see 2004 NHS Service Delivery Organisation document) [lv], [lvi], [lvii], [lviii].

- To prepare for an increase in dementia prevalence, in the context of limited care beds in the Borough, WLA could review capacity to increase the number of care beds available locally.

- Consider the geographical distribution of dementia need described within this report when commissioning services, including potential obstacles to accessing different sites (e.g. transport links).

- Recognising the lack of engagement of those directly affected by dementia in this document, people with dementia and carers for people with dementia should be actively involved in any future actions.

- WLA could review the potential for the local authority to support in improving care home quality in the borough in-line with national guidance.

Appendix

Wandsworth GP practice name: practice code key

References

[1] Informal carers are people who provide care on an unpaid basis.

[2] In Wandsworth there are no local authority owned care homes available, all care home beds are provided by other organisations.

[3] Additional factors include phenomena such as migration which are not explored in detail in this report.

[4] Based on 2017 Annual Population Survey.

[5] Estimates for high blood pressure and obesity PAF may be an underestimate as all-age hypertension and obesity prevalence is used, not mid-life prevalence.

[6] The risk factors listed for depression are not established as causative.

[7] A referral is made for a formal carers assessment

[8] 100,000 members of the general population.

[9] This includes ‘mixed Alzheimer’s dementia’.

[10] The Department of Health have produced guidance on how to construct care plans for those with dementia (https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/dementia-good-care-planning-v2.pdf).

[i] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NG97. June 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97

[ii] National Health Service. Dementia Guide. June 2017. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dementia/about/

[iii] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Dementia. May 2017 [Cited 15 Oct 2018]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/dementia

[iv] Office for National Statistics. Deaths registered in England and Wales (series DR): 2017. [Cited on 13 Nov 2018]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregisteredinenglandandwalesseriesdr/2017

[v] ONS, Deaths registered in England and Wales (series DR) 2017. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregisteredinenglandandwalesseriesdr/2017

[vi] Department of Health. Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. 2015 [Cited 16 Oct 2018]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf

[vii] Public Health England. Dementia: applying All Our Health. Jan 2018 [Cited 16 Oct 2018]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dementia-applying-all-our-health/dementia-applying-all-our-health

[viii] Public Health England. Pharmacy: A Way Forward for Public Health, Opportunities for action through pharmacy for public health. September 2017. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643520/Pharmacy_a_way_forward_for_public_health.pdf

[ix] National Health Service. NHS Long Term Plan. January 2019. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/nhs-long-term-plan.pdf

[x] National Health Service. Five Year Forward View. October 2014. [Cited 09 Nov 2018]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

[xi] Public Health England. Health matters: midlife approaches to reduce dementia risk. Mar 2016 [Cited 16 Oct 2018]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-midlife-approaches-to-reduce-dementia-risk/health-matters-midlife-approaches-to-reduce-dementia-risk

[xii] Department of Health & Social Care. Care Act. 2014. (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted)

[xiii] Department of Health and Social Care. Carers Action Plan 2018-2020. [Cited 14 Nov 2018]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/713781/carers-action-plan-2018-2020.pdf

[xiv] Institute of Public Care. Projecting Older People Population Information. [Cited 24 Apr 2019] Available from: http://www.poppi.org.uk/index.php [Password required

[xv] House of Commons Library. Constituency data: how healthy is your area? January 2019. Available from: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/social-policy/health/diseases/constituency-data-how-healthy-is-your-area/

[xvi] Knapp M, Prince M et al. Dementia UK, the full report. 2007. [Cited 15 Nov 2018]. Available from: http://www.the-debenham-project.org.uk/downloads/articles/dementiauk.pdf

[xvii] Wandsworth Local Authority. Mosaic adult social care database. 2019.

[xviii] Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia UK, second edition. 2014. Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59437/1/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

[xix] HM Prison & Probation Service. Justice. Wandsworth Prison information. Updated 22 Feb 2018. Available from: http://www.justice.gov.uk/contacts/prison-finder/wandsworth

[xx] Brooke J, Diaz-Gil A and Jackson D. The impact of dementia in the prison setting: A systematic review. Dementia. Sep 2018. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1471301218801715?rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&journalCode=dema

[xxi] Institute of Public Care. Projecting Older People Population Information. [Cited 11 Nov 2018] Available from: http://www.poppi.org.uk/index.php [Password required]

[xxii] van der Flier WM and Scheltens P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2005. 76(5). Available from: https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/76/suppl_5/v2

[xxiii] Wandsworth Local Authority. DataWand. https://www.datawand.info/

[xxiv] Prasher VP and Mahmood H. Management of Dementia in Intellectual Disability. Chapter 11: 136-137. Seminars in the Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability. 2019 Cambridge University Press

[xxv] Head E, Powell D, Gold BT and Schmitt FA. Alzheimer’s Disease in Down Syndrome. Eur J Neurodegener Dis. 2012; 1(3): 353-364. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4184282/

[xxvi] Institute of Public Care. Projecting Adult Needs and Service Information. Available from: http://www.pansi.org.uk/index.php?pageNo=390&areaID=8640&loc=8640 [Password required]

[xxvii] Strydom A, Hassiotis A, King M and Livingston G. The relationship of dementia prevalence in older adults with intellectual disability (ID) to age and severity of ID. Pyschological Medicine. Jan 2009 39(1): 13-21.

[xxviii] Wandsworth Local Authority. DataWand. https://www.datawand.info/

[xxix] Primary Care Mortality Database. 2016

[xxx] Greater London Authority. Central Trend Based population projections. Age range creator 2016. [Accessed on 25/03/2019]. Available from: https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/gla-population-projections-custom-age-tables.

[xxxi] National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Dementia Risk factors. May 2017 [Cited 19 Nov 2018]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/dementia#!backgroundsub:2

[xxxii] Public Health England. Public Health Profiles. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/

[xxxiii] Cataldo JK, Prochaska JJ and Glantz SA. Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010; 19 (2): 465-480. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2906761/

[xxxiv] Chen, H., Kwong, JC., Copes, R., Hystad, P., van Donkelaar, A., Tu, K., Brook, JR., Goldberg, MS., Martin, RV., Murray BJ., Wilton, AS., Kopp, A. and Burnett, RT. Exposure to ambient air pollution and the incidence of dementia: A population-based cohort study. Environ Int. 2017 Nov; 108:271-277. [Accessed online] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28917207

[xxxv] Carey, IM., Anderson, HR., Atkinson, RW., Beevers, SD., Cook, DG., Strachan, DP., Dajnak, D., Gulliver, J. and Kelly, FJ. Are noise and air pollution related to the incidence of dementia? A cohort study in London, England. BMJ Open. 2018 Sep 11;8(9). [Accessed online] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30206085

[xxxvi] Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. UK Air. Local Authority Details, London Borough of Wandsworth. Available from: https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/aqma/list

[xxxvii] Public Health England. British Social Attitudes: Attitudes to dementia. 2015. Available from: https://www.natcen.ac.uk/media/1264339/d%C2%A3mntla.pdf

[xxxviii] Enable leisure and culture. AL October 2017 – September 2018. [Cited on 13 Nov 2018].

[xxxix] Active Lifestyles Programme. Summer 2017. Available from: https://enablelc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Active-Lifestyles-Brochure-2017-NEW-Updated-Contact-Details-25.04.18.pdf

[xl] London Borough of Wandsworth. Adult Social Care, Market Position Statement. 2018/19.

[xli] South West London STP. Care Home Data Pack. September 2018.

[xlii] National Health Service England. Hospital Episode Statistics. 2018.

[xliii] NHS Digital. Recorded Dementia Diagnoses – January 2019. 12 Feb 2019. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/recorded-dementia-diagnoses/january-2019

[xliv] Cook, L., Mukherjee, S., McLachlan T., Shah R., Livingston, G., Mukadam, N. Parity of access to memory services in London for the BAME population: a cross-sectional study. Aging & Mental Health. 12 Mar 2018 [Cited 16 Oct 2018]. [Accessed online] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13607863.2018.1442413?journalCode=camh20

[xlv] Alzheimer’s Society. LGBT: Living with dementia. [Online; Accessed Mar 2019] Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/daily-living/lgbt-living-dementia

[xlvi] Office for National Statistics. Sexual Identity, subnational. 19 April 2017. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/sexuality/datasets/sexualidentitysubnational

[xlvii] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia, disability and frailty in later life – mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset. NG 16. 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng16

[xlviii] Nation Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NG 97. June 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97